Virginia Monument, Gettysburg (1917)

As the debate over the future of Confederate monuments has reached a fever pitch in the past two weeks following the events in Charlottesville, there have been calls to reconsider the placement of Confederate monuments in locations all over the country. From town squares to the halls of the U.S. Capitol, the continued presence of these monuments has been called into question. There have even been allusions to the Confederate monuments of Gettysburg, most of which were built in the early to mid-twentieth century, and questions as to whether these statues should be allowed to remain.

The National Park Service has weighed in on the issue, and for now, these statues will stay where they are. As Katie Lawhon, park spokeswoman, says:

Gettysburg National Military Park preserves, protects, and interprets one of the best marked battlefields in the world.

Over 1,325 monuments, markers, and plaques, commemorate and memorialize the men who fought and died during the battle of Gettysburg and continue to reflect how that battle has been remembered by different generations of Americans.

Many of these memorials honor southern states whose men served in the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. These memorials, erected predominantly in the early and mid-20th century, are an important part of the cultural landscape.

The National Park Service is committed to safe guarding these unique and site-specific memorials in perpetuity, while simultaneously interpreting holistically and objectively the actions, motivations, and causes of the soldiers and states they commemorate.

Longstreet Monument, Gettysburg (1998)

I think this is basically the right call. A battlefield is not the same sort of space as a town square, and monuments on a battlefield do not have the same connotation as monuments in civic sites. On a battlefield, monuments are commemorations of the specific actions that happened there, and at a site like Gettysburg, which is so well-marked by monuments, they can serve as interpretive tools for visualizing the events of the past. Confederate monuments at Gettysburg definitely perform these functions.

But more importantly: as it stands, Gettysburg’s commemorative landscape is a huge middle finger pointed directly at the South.

Why? Back in the 1880s, when the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA) was first working to preserve the battlefield, they knew they had to come up with a set of regulations for the type and placement of monuments that veterans’ groups were clamoring to install on the battlefield. One of the rules they devised was the “line of battle” rule, which stipulated that all units or states must place their monuments on the field at the location where they entered into battle, and not at any other spot. This had a huge impact on the eventual location of Confederate monuments.

As Thomas Desjardin explains:

The “line of battle” rule acquired great significance in the years to follow. Essentially, it required that veterans place monuments on the spot where they “entered the fight,” the definition of this to be ultimately determined by the GBMA. One benefit of this policy was that it squelched efforts by Confederate units to place monuments on parts of the field where key action occurred. Since the Union forces fought a largely defensive battle and allowed the Confederate forces to do the attacking, Southern battle lines were a great distance away from the ground on which they eventually met the Union forces and fought. Thus the Confederate units entered the fight as much as a half mile away from the areas of the battlefield where most of the fighting took place. Their monuments, in reflecting this, would not be located in the areas most sought after by those who would visit the fields in the decades to follow.

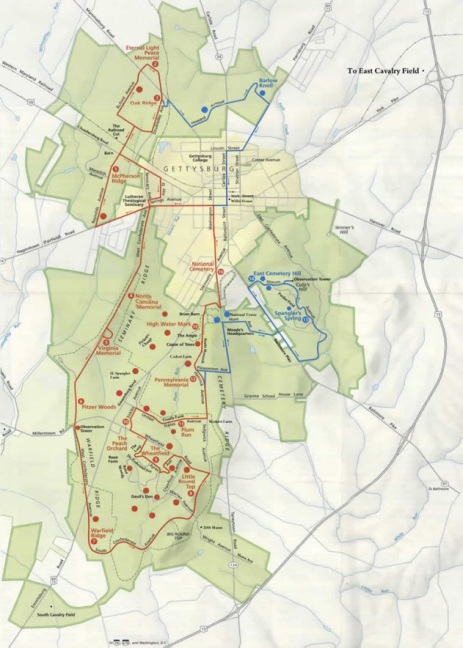

Click here for a larger version of the NPS Auto Tour map of Gettysburg.

In other words, the GBMA designed its regulations in order to prevent Confederate veterans’ groups from placing their monuments anywhere near the most important sites on the battlefield. Except for two small markers at the High Water Mark, the vast majority of Confederate monuments are sited along Seminary Ridge, where no major fighting took place. Meanwhile, the legendary sites along Cemetery Ridge that are the stuff of every Civil War buff’s dreams – Little Round Top, Devil’s Den, the Peach Orchard, the Wheatfield, the Angle, Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill – are largely Confederate-free. Thus, when visiting Gettysburg today, the visual landscape clearly shows the evidence of the GBMA’s efforts to stick it to the Confederacy in any way possible. The Confederate monuments may look impressive, but their placement on the field tells a different story.

So go ahead, Neo-Confederates, enjoy your participation trophies on Gettysburg’s second most important ridge. I’ll keep doing what I do every time I visit Gettysburg: I’ll drive down the Taneytown Road to the Union side, and avoid the Confederacy entirely.