Another one of my academic publications is finally seeing the light of day! In the latest issue of Public Art Dialogue, released over the weekend, you will find “From Spray Cans to Minivans: Contesting the Legacy of Confederate Soldier Monuments in the Era of ‘Black Lives Matter'”, an article I drafted last summer on the controversy surrounding Confederate monuments in the wake of the tragic shooting in Charleston. The article is part of a special issue of the journal titled “The Dilemma of Public Art’s Permanence,” organized and edited by Erika Doss to explore the afterlives of public artworks in a sphere of ever-changing public opinion. The special issue was inspired by a panel at the College Art Association in 2014, in which I participated. When the Charleston shooting brought the continuing existence of Confederate monuments to the forefront of public consciousness last summer, I already had the existence of this special issue on my radar, and I was grateful for the opportunity to think through some of the issues surrounding these memorials.

Another one of my academic publications is finally seeing the light of day! In the latest issue of Public Art Dialogue, released over the weekend, you will find “From Spray Cans to Minivans: Contesting the Legacy of Confederate Soldier Monuments in the Era of ‘Black Lives Matter'”, an article I drafted last summer on the controversy surrounding Confederate monuments in the wake of the tragic shooting in Charleston. The article is part of a special issue of the journal titled “The Dilemma of Public Art’s Permanence,” organized and edited by Erika Doss to explore the afterlives of public artworks in a sphere of ever-changing public opinion. The special issue was inspired by a panel at the College Art Association in 2014, in which I participated. When the Charleston shooting brought the continuing existence of Confederate monuments to the forefront of public consciousness last summer, I already had the existence of this special issue on my radar, and I was grateful for the opportunity to think through some of the issues surrounding these memorials.

Here is the abstract for my article:

In the wake of the shooting of nine parishioners of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina in June 2015, there have been calls to remove or reconsider monuments to the Confederacy in the United States. In addition, monuments have been targeted with graffiti linked to the “Black Lives Matter” movement. In order to decide how to deal with these phenomena, communities must understand the link between Confederate symbols, America’s racial past, and the current epidemic of police violence against black Americans.

This essay will explore the history of Confederate monuments from the Civil War to the present, including the relationship between Confederate symbols and the most violent aspects of the struggle for civil rights for all Americans. The discussion will then turn toward Reidsville, North Carolina, where a freak traffic accident in 2011 toppled the local Confederate soldier monument and forced citizens to confront their relationship with Civil War history. In exploring the history of Confederate symbols and the ways in which one town reckoned with them in recent years, this essay will provide necessary guidance for individuals and communities grappling with the legacy of Confederate memory in the age of “Black Lives Matter.”

CLICK HERE to access the article if you have access to journals through an academic institution.

If you would like to read the article but do not have this sort of access, you’re in luck! Taylor and Francis has offered me 50 free eprints of the article, available for a limited time. To download one of these eprints, CLICK HERE.

Citation: Sarah Beetham, “From Spray Cans to Minivans: Contesting the Legacy of Confederate Soldier Monuments in the Era of ‘Black Lives Matter.’” Public Art Dialogue 6, no. 1 (2016): 9-33.

It is a very old form, dating as far back as ancient Greece, where it was considered a suitable site for philosophical conversations. But during the Roman Empire, the exedra became particularly associated with funerary monuments. Placed alongside major thoroughfares, funerary exedrae offered the weary traveler a chance to sit and to take a break from the dusty road. In return for this courtesy, the traveler might take a moment to read the name of the deceased aloud – because in ancient Rome, a part of a man’s spirit remained alive as long as there was someone to speak his name.

It is a very old form, dating as far back as ancient Greece, where it was considered a suitable site for philosophical conversations. But during the Roman Empire, the exedra became particularly associated with funerary monuments. Placed alongside major thoroughfares, funerary exedrae offered the weary traveler a chance to sit and to take a break from the dusty road. In return for this courtesy, the traveler might take a moment to read the name of the deceased aloud – because in ancient Rome, a part of a man’s spirit remained alive as long as there was someone to speak his name.

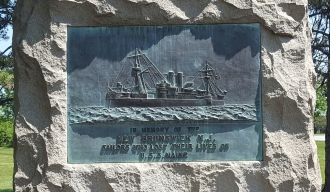

The first stop along my walk today was the Maine Monument, dedicated to three New Brunswick residents who died in the

The first stop along my walk today was the Maine Monument, dedicated to three New Brunswick residents who died in the  The opposite side of the stele features an inscription naming the sailors who perished in the sinking. Also included here is a howitzer captured from the Cabanas Fortress in Havana Harbor during the course of the Spanish-American War. With the inclusion of the howitzer, the monument is part cenotaph and part trophy: naming fallen soldiers whose remains probably lie far from this location, while showcasing an object taken during the course of the military action waged in response to their deaths. This mix of messages is not uncommon in monuments to the Spanish-American War, a war fought entirely overseas for mostly imperial aims that saw eight soldiers perish from disease for every one who succumbed to wounds on the battlefield.

The opposite side of the stele features an inscription naming the sailors who perished in the sinking. Also included here is a howitzer captured from the Cabanas Fortress in Havana Harbor during the course of the Spanish-American War. With the inclusion of the howitzer, the monument is part cenotaph and part trophy: naming fallen soldiers whose remains probably lie far from this location, while showcasing an object taken during the course of the military action waged in response to their deaths. This mix of messages is not uncommon in monuments to the Spanish-American War, a war fought entirely overseas for mostly imperial aims that saw eight soldiers perish from disease for every one who succumbed to wounds on the battlefield. For this reason, stopping to visit this monument proved to be a fitting beginning for my summer of writing. One of the pieces that I currently have in development concerns Theo Alice Ruggles Kitson’s Hiker, a stalwart bronze soldier of the Spanish-American War first erected in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1906, and subsequently copied in more than fifty locations across the United States. Created a few crucial years after New Brunswick’s Maine monument, Kitson’s Hiker is a strapping muscle man that embodies all of the war’s triumphs and none of its darker aspects. As I work my way back into this material, I will keep this local monument in mind.

For this reason, stopping to visit this monument proved to be a fitting beginning for my summer of writing. One of the pieces that I currently have in development concerns Theo Alice Ruggles Kitson’s Hiker, a stalwart bronze soldier of the Spanish-American War first erected in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1906, and subsequently copied in more than fifty locations across the United States. Created a few crucial years after New Brunswick’s Maine monument, Kitson’s Hiker is a strapping muscle man that embodies all of the war’s triumphs and none of its darker aspects. As I work my way back into this material, I will keep this local monument in mind. My visit to the site of the New Brunswick Maine monument yielded one other notable phenomenon. To the left of the memorial to the soldiers of the Maine were two additional markers, one honoring soldiers of Company E of the 114th Infantry, 44th Division of the New Jersey National Guard who fought in World War II, and the other naming several Catholic War Veterans of St. Sebastian Post 405 who perished in World War II and the Korean War. The latter tablet is dated 1958, the year that the Maine monument was relocated from the Court House to Buccleuch Park, and it would be interesting to know more about what led to the relocation of the monument and to the appearance of the additional markers.

My visit to the site of the New Brunswick Maine monument yielded one other notable phenomenon. To the left of the memorial to the soldiers of the Maine were two additional markers, one honoring soldiers of Company E of the 114th Infantry, 44th Division of the New Jersey National Guard who fought in World War II, and the other naming several Catholic War Veterans of St. Sebastian Post 405 who perished in World War II and the Korean War. The latter tablet is dated 1958, the year that the Maine monument was relocated from the Court House to Buccleuch Park, and it would be interesting to know more about what led to the relocation of the monument and to the appearance of the additional markers.  My larger book project, Monumental Crisis: Accident, Vandalism, and the Civil War Citizen Soldier, explores the processes by which monuments are sometimes damaged or altered during the course of their time in public life, whether through accidental or purposeful means. One of the chapters concerns revision, or the series of processes by which a monument or its site may be altered, moved, removed, or amended in order to change its meaning or allow for additional voices to be recognized. In thinking about this series of forces, I often wonder about the ways in which a war memorial honoring the soldiers of one war often begins to attract tributes to veterans of other wars, and how sites in which war in remembered eventually tend to take on multiple meanings and chronologies. I did not necessarily expect to find this particular phenomenon on my walk today, but I was glad for the opportunity to reflect on it.

My larger book project, Monumental Crisis: Accident, Vandalism, and the Civil War Citizen Soldier, explores the processes by which monuments are sometimes damaged or altered during the course of their time in public life, whether through accidental or purposeful means. One of the chapters concerns revision, or the series of processes by which a monument or its site may be altered, moved, removed, or amended in order to change its meaning or allow for additional voices to be recognized. In thinking about this series of forces, I often wonder about the ways in which a war memorial honoring the soldiers of one war often begins to attract tributes to veterans of other wars, and how sites in which war in remembered eventually tend to take on multiple meanings and chronologies. I did not necessarily expect to find this particular phenomenon on my walk today, but I was glad for the opportunity to reflect on it. The last monument site I encountered today is in a bit of a different category: the fireman’s memorial. This unusual memorial sits at the corner of Easton Avenue and Wyckoff Street in New Brunswick. Erected in 1931, it consists of a bronze statue of a firefighter displayed underneath a pergola with Corinthian columns. The statue stands atop a rough-hewn granite base carved with the words, “VOLUNTEER / AND EXEMPT FIREMEN / 1747-1941 / ERECTED AD 1931.” At the moment, I do not know any more about the circumstances surrounding this particular monument than I can see in that inscription.

The last monument site I encountered today is in a bit of a different category: the fireman’s memorial. This unusual memorial sits at the corner of Easton Avenue and Wyckoff Street in New Brunswick. Erected in 1931, it consists of a bronze statue of a firefighter displayed underneath a pergola with Corinthian columns. The statue stands atop a rough-hewn granite base carved with the words, “VOLUNTEER / AND EXEMPT FIREMEN / 1747-1941 / ERECTED AD 1931.” At the moment, I do not know any more about the circumstances surrounding this particular monument than I can see in that inscription. But I’ve long found firefighters’ memorials intriguing for their potential relationship with the citizen soldier monuments that form the basis of much of my research and writing. Both tend to feature single statues of generic figures meant to stand in for a particular population. Both have at times been mass-produced and sold in catalogues. Both allude to the virtues of self-sacrifice in the service of the good of the community, and as such both serve as didactic exemplars of civic responsibility when placed in public settings. When I think about my bucket list of future research projects, firefighters’ memorials definitely appear on the list, and I would love to learn more about them.

But I’ve long found firefighters’ memorials intriguing for their potential relationship with the citizen soldier monuments that form the basis of much of my research and writing. Both tend to feature single statues of generic figures meant to stand in for a particular population. Both have at times been mass-produced and sold in catalogues. Both allude to the virtues of self-sacrifice in the service of the good of the community, and as such both serve as didactic exemplars of civic responsibility when placed in public settings. When I think about my bucket list of future research projects, firefighters’ memorials definitely appear on the list, and I would love to learn more about them. In fall 2015, I taught the course “Women in American Art” at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. The course examined the contributions of American women artists to the history of art from the late 18th century to the present. For their semester-long project, I asked teams of students to write or improve Wikipedia articles on American women artists in order to increase the visibility of women on that platform. (

In fall 2015, I taught the course “Women in American Art” at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. The course examined the contributions of American women artists to the history of art from the late 18th century to the present. For their semester-long project, I asked teams of students to write or improve Wikipedia articles on American women artists in order to increase the visibility of women on that platform. ( In addition to my teaching responsibilities for the fall, I presented papers at two conferences. In early October, I traveled up to Toronto, ON for the American Studies Association, where I presented “Resorting to Reproduction: The Elbert County Confederate Monument and the Failure of Originality.” This was the first time I ever attended the ASA, and I was impressed with the range of panels of interest to scholars of visual and material culture. Later that month, I headed out to Pittsburgh to attend the Southeastern College Art Conference, one of my favorite events every year and a must for researchers in American art. My paper, “Toward a Manly Ideal: Kitson’s Hiker and the Spanish-American War,” marked the first time I have ever spoken in public about my work on Spanish-American War monuments. One of my goals this summer will be to submit some of that material for publication. At the end of October, I relocated from Delaware to New Jersey – a non-academic activity that took up a tremendous amount of my time!

In addition to my teaching responsibilities for the fall, I presented papers at two conferences. In early October, I traveled up to Toronto, ON for the American Studies Association, where I presented “Resorting to Reproduction: The Elbert County Confederate Monument and the Failure of Originality.” This was the first time I ever attended the ASA, and I was impressed with the range of panels of interest to scholars of visual and material culture. Later that month, I headed out to Pittsburgh to attend the Southeastern College Art Conference, one of my favorite events every year and a must for researchers in American art. My paper, “Toward a Manly Ideal: Kitson’s Hiker and the Spanish-American War,” marked the first time I have ever spoken in public about my work on Spanish-American War monuments. One of my goals this summer will be to submit some of that material for publication. At the end of October, I relocated from Delaware to New Jersey – a non-academic activity that took up a tremendous amount of my time!