It’s been an interesting summer so far. For the past few weeks, I’ve been doing a bit of freelance writing, working on a group of catalogue entries on important American sculptures for a major new show on American art. The project has been stimulating: it’s a bit of a break from ruminating over monumental destruction, and I’ve had the chance to research a number of works that were familiar to me, but which I had never taken the opportunity to think deeply about.

One of those is Frederic Remington’s Broncho Buster. Remington’s art has never particularly appealed to me: I find the machismo more than a little off-putting, and the politics inherent in his work are quite upsetting as well. Remington was active as an artist at a particular moment in American history when the conquest of the West was drawing to a close and the imperialist era, signaled by the Spanish-American War, was just dawning, and his cowboys and Indians are completely tied up in that narrative. There’s a reason that Remington was drawn to the activities of the Rough Riders in Cuba during the War of 1898, and there’s a reason that Teddy Roosevelt was so fond of his work. The two men really suited each other.

That said, the story of how Remington became a sculptor is compelling. In late 1894, the sculptor Frederic W. Ruckstull was staying with Remington’s neighbor, Augustus Thomas. At the time, Ruckstull was working on an equestrian statue honoring Major General John F. Hartranft, and Remington often went to watch him at work. One day, Augustus Thomas observed how Remington was able to imagine the same figure from multiple viewpoints on paper, mentally turning the subject one way or another to suit his needs, and pointed out that with skill like this, Remington had the mind of a sculptor. Remington agreed, and with the encouragement of Ruckstull and Thomas, he began working in clay and finished The Broncho Buster shortly afterward. As a first effort, it is extraordinary, with dynamic action and virtuoso use of space. The sculpture went on to be one of the most popular in turn-of-the-century America, with hundreds of authorized and unauthorized casts.

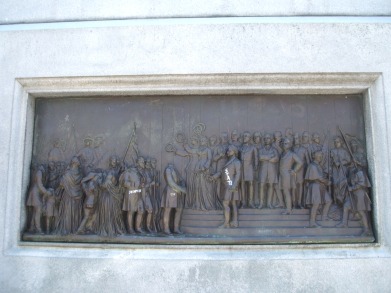

James Edward Kelly, Defenders of New Haven (detail), New Haven, CT, 1910: This monument’s condition shows that bronze definitely does NOT endure forever!

While working on the sculpture, Remington made a striking statement in a letter to his friend, the novelist Owen Wister:

My water colors will fade—but I am to endure in bronze—even rust does not touch. I am modeling —I find I do well—I am doing a cowboy on a bucking broncho and I am going to rattle down through all the ages, unless some Anarchist invades the old mansion and knocks it off the shelf.

In other words, Remington was drawn to work in sculpture because he felt the medium made his work immortal. Of course, as a researcher with a keen interest in the destruction of sculpture, this jumped out at me. The whole premise of my book project is to undermine popular perception of monumental sculpture as permanent, unchangeable and unchanging. Bronze and stone sculptures change all the time, especially when they are outdoors. The materials weather over time and are subject to deliberate and accidental damage. Sometimes they are removed or relocated, either for political or practical reasons. For all of these reasons, sculpture is not the enduring substance of fame through the ages that Remington imagined in his letter.

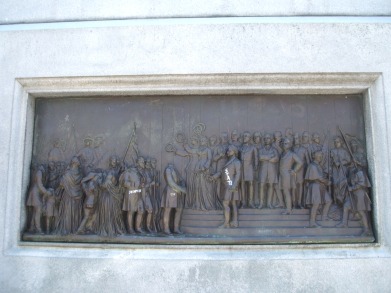

Martin Milmore, Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument (detail), Boston Common, Boston, MA, dedicated 1877: Remington’s anarchists?

But it’s also interesting that Remington imagined unnamed “Anarchists” as the possible downfall of his plan for immortality. As we’ve seen with Confederate monuments in recent months, the extralegal activities of actors opposed to a monument’s message can indeed cause lasting damage. The current move to replace or remove Confederate monuments has been ignited for multiple reasons, but chief among them is certainly the actions of individuals who no longer wish to allow the monuments to exist in their communities, and will ensure that their wishes are carried out by force if necessary. Remington’s politics certainly would not be aligned with today’s American Left, and if his cowboy sculptures had ever become monuments, they might be on the chopping block today.

I’m going to think about Remington in relation to my book project a bit more, and some of these thoughts might be making their way into the text somewhere. In all, this week has reminded me that sometimes it’s useful to step away from one’s main project in order to work in other directions for a little while. One never knows what might come from pursuing another path.