A few weeks ago, I taught a lecture on surrealism to my Introduction to Art History students at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Of course, one of the works we discussed was René Magritte’s famous provocation, The Treachery of Images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) of 1929. You know the one: a picture-perfect illustration of a pipe with words in French that translate to “This is not a pipe” written beneath it. In case you need a refresher on the meaning of the original painting, here’s a great summary video by Beth Harris and Steven Zucker of Smarthistory:

As Harris and Zucker explain, this painting can be interpreted in several different ways. First, of course, there’s the obvious: Magritte is correct that this is not a pipe, because it is a painting of a pipe, making it a representation and not the real thing. Up until the early twentieth century, Western artists had been concerned mainly with illusionistic representations of the natural world, and with this painting, Magritte upends centuries of tradition. One might even see this painting as an attack on the very notion of language itself, as the word “pipe” is not an actual pipe any more than Magritte’s painting is: both are symbols that stand in for the real thing.

But there’s another way of looking at this painting that I think might be telling for some of our current discussions surrounding monuments today. Magritte gives us a perfect painting of a pipe, and a text that says it is not a pipe: which do you believe? Which message is stronger? Do you respond more to the tangible image, or the text? What does this tell us about words and images today?

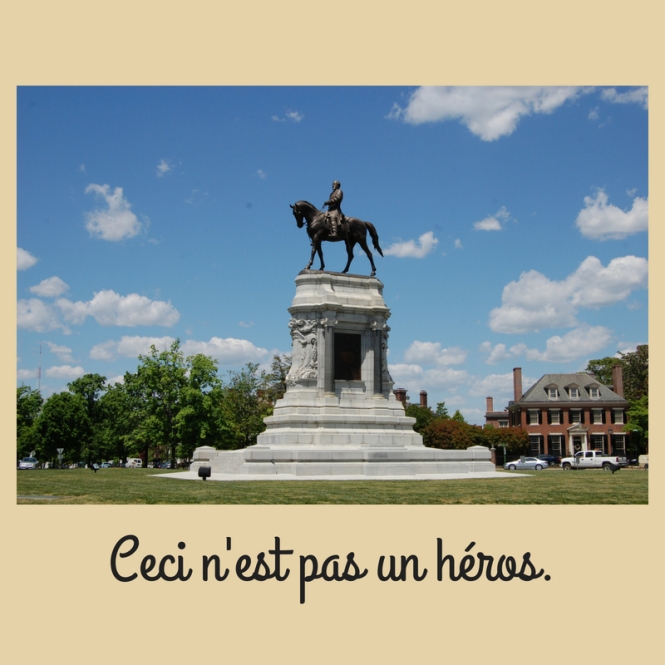

When I look at this painting, I am powerfully reminded of the notion of recontextualizing problematic monuments by adding new plaques or inscriptions to place them alongside the darker aspects of their historic background. This has been suggested in some circles as an alternative to removing the monuments, as a way of preserving the built environment while providing necessary information about the past. I’ve long felt that this was not a workable strategy, and I think Magritte tells us exactly why. In other words:

Which is more powerful, the image or the text? Do you believe the equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee set on a towering pedestal, one of the enduring symbols of heroism and power in Western art, or do you believe the text that tells you he is not worth celebrating? Is there any text or any plaque that could possibly counteract the visual impact of a monument? Or will the text always fade into the background?

To my mind, there’s no way to insert text alongside a monument that would counteract the power of the visual symbol, unless that text is written on a billboard or superimposed on the monument in some way. The equestrian statue and the triumphal column are too ingrained in our collective cultural heritage to allow for disruption in text. If we are going to seek just representation in our public spaces, we will have to find another way.

A few weeks ago, I was invited to participate in a historian roundtable by the

A few weeks ago, I was invited to participate in a historian roundtable by the